Here is the result of a test, where the failure point of the

3/16” National Hardware rapide was definitely above 4044 (+/-40) lbs. I pulled

the rapide between two HMPE soft shackles. One soft shackle was attached to my

jeep via a 3’ piece of 5/8” nylon rope, supposedly rated to at least 8000 lbs,

but tied in figure-8s on bights for the connection. The other soft shackle was

attached to a linescale 3 load cell on a fixed anchor. The rope broke at the

knot, and the rapide was not even deformed. The stated WLL of this rapide is 1150

lbs. The breaking strength is presumably n*1150 lbs., where n is 3-5. Below are

some “after” photos.

I’d done a similar test over a year before, also with a

National Hardware rapide where I got to 3280 lbs, when the rope broke first, and the

rapide was fine.

So

why is there so much hate on the web for these small, non-PPE

rapides? Partly, people don't realize they can be much stronger than

other parts of their system. Then there is just the “lore” that

unmarked rapides are always bad; and small rapides are much less likely to be marked.

There is less area to put a numbers on a small rapide, the surface is

highly curved, and the writing (whether by stamping or laser etching) adds cost. (Péguet

does stamp 3/16" rapides, but the writing is barely readable, and is on

the inner surface; US Stainless stamps just the steel type.) People take boxes of anonymous rapides they

bought off eBay, search for the mankiest-looking piece, and then show break

tests. Huh.

Bear in mind that your harness belay loop is rated to just

3500 lbs, and it is doubtful you would survive 3500 lbs on your hips without serious

spinal damage.

I don’t mean to single anybody out; you will find similar opinions

all over the web. But let’s look at comments from a clear canyoneering expert

(whom I respect; I emphasize I respect him, but sometimes we disagree).

“What you are looking for are Rapid Links (aka Rapides, Quick Links, Maillon Rapide, Links). Available in many styles and sizes. The cheap ones are junk, meaning, they have no brand name on them, and their quality varies widely... and they are not really made for life-safety applications. These no-brand rapides are often referred to as "Pacific Rim", and are available at Home Deport, Harbor Freight, etc... I recommend against using non-brand-name hardware for life safety applications.”

I agree that the sort of hardware store rapides that one used

to find in a bin could vary a lot in quality; but I haven’t seen those bins in

years. I’m also pretty sure the author of this comment did not judge

the variation based on his own break-testing, and the idea probably spans observations of links

from a myriad of sources. Today most stores sell plastic-closed cards with one

rapide apiece, at about 2x the price of the old “bin” rapides, like so:

National Harware is a big company with its own QA policy; they publishes spec pdfs-- e.g. for 3/16" quicklinks.

Here’s where you need to do your own QA/QC. No matter the

brand, you need to examine the area that’s most like to have failures: the

threads on/in the male and female sides of the nut. Partly open the rapide, and

spray PTFE dry lube on the "male" threads and into the nut threads. You should be able

to tighten the nut easily but firmly, so no thread is left showing. Do this

several times.

Three years back, I bought 3/16" (5mm) rapides from three sources (Lowe’s

National Hardware, Péguet, and US Stainless) in batches of ten, then subjected three

from each batch to a pull to at least 1000 lbs (after the PTFE treatment

above). After weighting, I was always able to unscrew the rapide with finger

strength, or in one case (a Péguet rapide), light crescent wrench force.

Some thoughts QA/QC for those stamped rapides

Here's what the Péguet Maillon Rapide catalog says about their

QA/QC: “Quality control throughout the manufacturing process is made

through internal control procedures. Quality materials from our raw material

suppliers is fundamental. A monitoring plan makes it possible to ensure a

variety of controls on the entire production process. The final check allows us

to offer top of the line products. In particular, our manufacturing of

stainless steel is subject to unit control of the products.” OK, what exactly

does that mean?

Well, here's what Lowe's says: "In 2016, more than 13,000 product tests

were conducted in 87 third-party labs around

the world.

The Quality Assurance team also works

closely with third-party agencies to conduct

preshipment product inspections prior to

acceptance by Lowe’s. Products are inspected for proper labeling, functional operation

and consistency across production samples to help ensure customer satisfaction.

In 2016, factories were visited nearly 11,000

times to perform these preshipment product

inspections."

Note that most Péguet rapides sold are NOT certified for PPE. And “certified for PPE” does not mean that occasional screwups won’t leak through:. Edelrid recalled PPE-certified rapides made by Péguet, because some looked like this:

Would 5mm rapides cause undue force for rope pulls?

Again, from

the respected canyoneering site: “I sell Rapides made by a French company with

excellent quality control called Maillon Rapide. They come in many sizes, and

the 7mm seems to be a good balance of weight vs. strength and working size.

Some people use the 6mm (especially for explorations), but they are small

enough that the fattest ropes people might take into canyons might get stuck in

the pull. The 8mm size is good for high-use canyons, but they are heavy. Larger

rapides are not only quite heavy, but also may be big enough to let a biner

block slip through.”

A minor note: “Maillon Rapide” is simply French for “Quick Link;”

I’m not sure this is a brand. Péguet started using this term about 1940, but the

name “quick link” has been used for the same product from other manufacturers

for a long time. The “Maillon Rapides” that people respect are made by Péguet

in France. Similarly, “Crescent Wrench” and “Channellock Pliers” are registered

names, but we all use those terms for tools made by other companies.

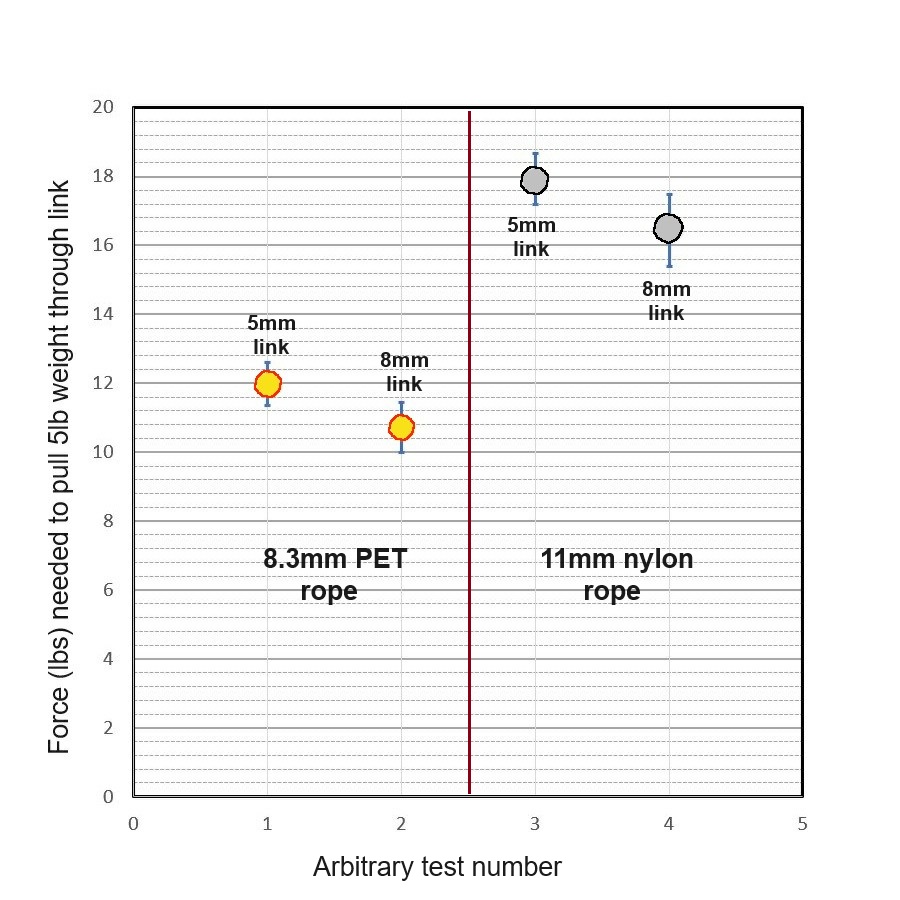

Let’s look at the forces required to pull 8.3mm polyester and

11mm nylon (dynamic) ropes through 5mm and 8mm rapides:

You

can see the thickness of the rope made the greatest

difference; the size of the rapide was a relatively minor effect.

Possibly some of the extra force required for the 11mm dynamic rope,

is taken up by the energy of stretching. The

inefficiency of the pull over the 5mm link is a little greater – but

comparable

– to the inefficiency of pulling a rope over a carabiner. A 13mm rope

(13mm is

the inner diameter of curvature of a 5mm rapide) certainly will get

stuck; but

I don’t know any canyoneers who use ropes over 10mm.

How was the test done? I used a 44x2 lb AWS (CE-certified) hanging

scale, calibrated on small dumbbell weights. To record the forces,

I took videos of the digital screen with my smartphone attached to the

scale

through a flexible tripod.

Each

point on the plot represents 4 pull tests (hence the error bars). To

get a value for each of the four tests at each point on the plot, ~20

times were used to define the “plateau" on a single pull test, and I

averaged the 3 highest values from each plateau. I had the rapides hung

from the top of my

stairwell, and had ~20’ of rope up and through a rapide “pulley,” down

the

other side. The far side had a 5lb dumbbell, and I walked down the

stairs on

the other side, trying to maintain an even rate as I raised the

dumbell. The force went up as the weight was lifted, plateaued, then

went down

at the end of the test.

The same canyoneering web site recommends an anchor tied with

an overhand on a bight, hanging off one strand of webbing. Now, I use this type

of anchor, and think is great for canyoneering-type raps. Assuming

1” climbspec tubular nylon webbing, the breaking force at the knot would be

<2500 lbs. That’s plenty for most canyoneering

rappels… but wouldn’t a 4000 lb-breaking-strength rapide be more than enough?

Do you think there are many rapide failures in canyons?

What are the “well-documented” cases of rapide failure in a

canyon? I’ve searched hard on this; maybe I’m just using the wrong terms. I

find just one case in the Blue Mountains of Australia, in a Péguet-made rapide. The

failure was probably due to two factors: 1) to a minor extent, use of a delta

versus an oval rapide; and 2) failure to close the gate. There are conflicting

reports about the gate, possibly because no one wants to take the blame for screwing-up. In canyons with

lots of fine sediment, it is easy to get grit on a rapide threads, making the rapide hard to close.

I have personally seen a case where someone opened the rapide,

then closed it over just a few threads. I had been there a few months before,

and had left it completely closed; and I know one other party came by in the

interim, and apparently opened and partly closed the rapide. Always check.