Rockfall and cut slings

When travelling light, I bring thin, 1/8” (3.2mm) 12-braid UHMWPE (generic Dyneema) slings. I use “class 2" bury splices to make eyes on each end. My tests give a breaking strength of 2400 to 2700 lbs when these slings are pulled end-to-end (eye-to-eye). However, my friends often express worry that the thinness of these slings makes them susceptible to cuts “from rockfall;” they are generally more comfortable with 16mm nylon tubular webbing (2200-2400 lbs unknotted; but substantially weaker with a knot).

It is pretty hard to test the relative cut-resistance of

these slings, since the rockfall scenario has so many parameters. If one drops

a 500 lb rock from 20’, and it hits just right, it will sever any polymer rope,

and might even sever 1/4” stainless steel cable. So the test described below is

scoping in nature, and merely intends to give a feel for the relative

resistance of the two sling types. The

results mainly give me hints how I would design a more meaningful test.

The test: I had two textured concrete (with silica sand

fill) landscaping pavers gorilla-taped together, to make an 8” by 12” “anvil.”

Across the 8” width, I placed either 6 pieces of 16mm nylon webbing on 16mm

centers, or 6 pieces of 1/8” (3.2mm) UHMWPE on 16mm centers. From 5.0’ above

this anvil, I dropped a 3.0 kg rock, 15 times for each set. (I had previously

practiced so I could consistently get the rock to fall near the middle of the

anvil each time.)

Since I wanted the slings to have full strength, I sewed

eyes on the ends of the nylon slings

with 540 stitches of Mara 50 thread (5.3

lb tensile strength), resulting in > 4000 lbs strength for the eye

stitching.

A test breaking a new piece (so sewn) gave 2334 lbs at breaking, quite

close to

the manufacturer’s (Bluewater) specification of 2200-2400 lbs. (The

break did not occur in the sewn ends, but in the middle of the sling.)

For the UHMWPE, I

used class 2 bury splices on each end, with ~14 (not tight) stitches of

100 lb

woven spectra fishing line to prevent the ends from accidental

unburying. A

test sample of new UHMWPE line gave ~2700 lbs at breaking.

Here's what this rock (a massive serpentine marble) looked

like after the tests:

The rock started at 3.03 kg, massed 3.02 kg at the end of the 1st test (with 16mm nylon), and 2.99 kg after the 2ndtest. In the second test, I could see a few flakes of rock breaking off, making the edges sharper. You can see the powdery impact marks on the right photo.

Here’s what the slings, on the same landscaping pavers, looked like after the test:

The arrow points to a place where the rock hit

twice;

I refer to this as the “unlucky section” of UHMWPE. In one impact at

this spot, a small fragment of rock broke off and stayed right at the

impact site; a subsequent drop hit on top of this rock fragment.

After the test, each sling was pulled to breaking with a

come-along, the force measured by a crane scale.

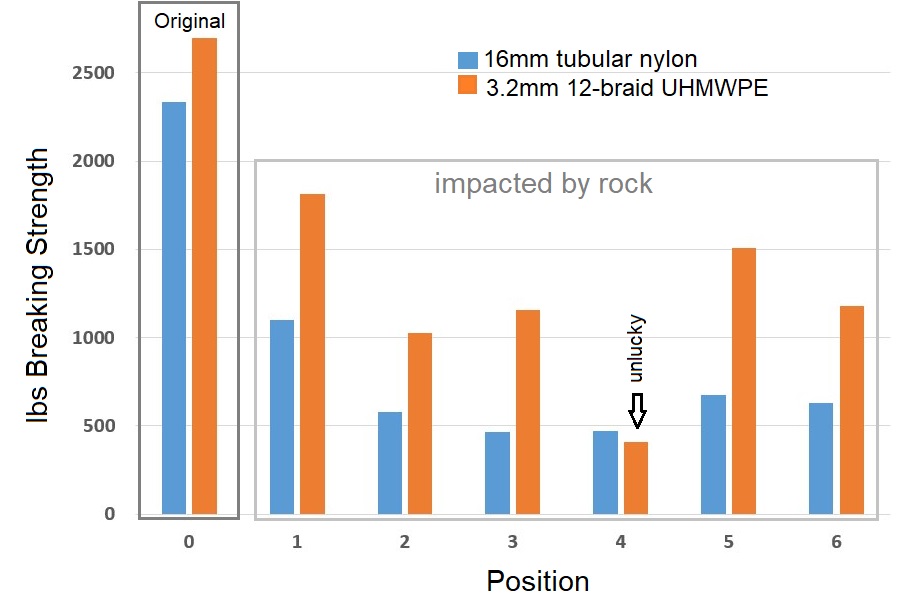

Here’s a plot of the results:

The UHMWPE did relatively well compared to the 16mm nylon;

but none of the results are really “good.” As expected, the UHMWPE that was

“double-hit” in one place broke at a rather low tension. A “surprise” was the

rather low breaking strength of 16mm nylon sling 1; this sample seemed to have

only a slight nick at the junction with sling 2. However, since

tubular webbing has no guard thread running near the edge, it doesn’t take much

to cause a catastrophic tear from one point of compromise.

If I were to repeat the tests, I would:

1)

Use more replicates;

2)

Drop several smaller (1 kg) rocks at once,

through a 6” diameter plastic pipe, with a hopper feed;

3)

Alternate nylon and UHMWPE samples to minimize

bias from the degradation of the substrate and falling rocks;

4)

Repeat this all with the anvil tilted 45 degrees

to horizontal, to achieve a more “glancing” blow;

5)

Use a better load cell with higher time

resolution for the break tests.

The type of rock dropped would be a mix of local limestone,

basalt scoria, or sandstone chunks, with a bias to selecting more equant rocks

with less dramatically sharp edges. Originally the impact surface had textured

indents “ledges” running perpendicular to the webbing; I felt the texture would

be more representative of harsh conditions and might cut the straps from below.

I would probably still use this surface, though it does seem the worst damage

was mainly on the dropped-rock impact side of the slings.

There is a concern that rockfall will cut webbing

and rope

used in climbing. I have seen several handlines that were apparently

cut by

sharp limestone rock fragments; I actually witnessed ~100 lbs of rock

fragments

(knocked down by another climber) fall and sever a 16mm webbing

handline, whose

end was about 20’ below us, on a talus slope below a cliff. I’ve also

found a

rope handline, severed by spring rockfall off of a limestone cliff. I

understand these concerns, especially for people who climb in areas

that have

heavy snows, and freeze-thaw cycles. In both cases, the cuts were not

near the anchor, but were below the cliff on the talus slope, where

rocks could fall off the cliff for a substantial distance and inpact

the "loose end" of the soft goods.

The evidence for slings cut by rockfall

First, I am a fan of redundancy in anchors, especially when

it is easy to do. When there are two bolts, by all means clip each so there will

still be one weight-sustaining point, if the other fails. I guess I came from a

time when bolts were often untrustworthy and many anchors were on pitons. But

lately, most people seem to want redundancy in the slings, not because of worry

about the actual metal-rock connection, but because of the possibility that a

soft-goods sling will be cut by rockfall.

There are anecdotal examples of people being saved by sling

redundancy, after one leg was cut by rockfall. One of the more popular examples is given in

this thread:

https://www.mountainproject.com/forum/topic/110088639/rock-fall-results-in-chopped-anchor

Big And Little Cottonwood Canyons are adjacent in the

Wasatch (SE of Great Salt Lake),

on N and S sides of a quartz monzonite ridge. "The Thumb" routes (site

of the accident) comprise one set of climbs in Little Cottonwood

Canyon.

Note

that they were climbing on a warm

February day, in an area known for severe rockfall, in times when the

snow is

melting above. The area gets cold at night, and frost wedging

undoubtedly occurs, so rocks cut loose after the sun warms the rocks.

Note also that the anchor that they

clipped had previously been smashed by rockfall.

Of 122 climbs logged in Mountain Project

alone for general thumb, 88 for this variation, this is the only one to mention

rockfall (as of the date of this article). The logs generally don’t mention other partners. A microwave-sized

fragment of granite (my microwave is 24” by 18” by 13” without legs) would

weigh 500 lbs, so the original boulder, which had at least three such

fragments, may have been 2000 lbs. HOWEVER, there have been many reports of

rockfall-caused deaths and accidents in the areas of Big and Little Cottonwood

Canyons; the people who were killed or severely injured probably didn’t log in

to report their climbs

The AAC analysis of the accident is here:

http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13201213756/Rockfall-Anchor-Chopped

In April, 2018 (2 years later)

another climber (on thumb) had to bail when rockfall damaged his rope.

Recently, a woman (wearing a helmet) was walking to a climb

in Little Cottonwood and hit by rock:

it seems that she eventually died.

Another woman was killed by rockfall in Big Cottonwood

Canyon, Utah while belaying her partner; as a rleatively minor point, the rope was cut by rock.

https://www.climbing.com/news/one-killed-another-rescued-in-utahs-big-cottonwood-canyon/

The survivor (her boyfriend, also very injured) pleads for people not to climb

“early” in that area (his fateful climb seems to be in May):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YzS9V_ArXfk&ab_channel=KUTV2NewsSaltLakeCity

Here’s the report of another climber killed by falling rock

in Little Cottonwood Canyon:

https://www.sltrib.com/news/2021/10/11/rock-climber-killed-fall/

Climbing in the Cottonwood Canyons, especially early in the

season, seems to have exceptional danger from falling rock. Many studies, for various OTHER areas, come

up somewhat differently:

4.5% of climbing accidents from rockfall:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6981967/

Broad analyses of rock-climbing fatalities

https://blog.gitnux.com/rock-climbing-death-statistics/

https://www.improve-climbing.com/how-dangerous-is-climbing/

falling rock cause of over 26% of climbing fatalities, 7 %

injuries+ fatalities

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/ham.2021.0085

falling rock and ice 21% (of those, 56% head trauma)

https://bmjopensem.bmj.com/content/8/1/e001281

My general take is this. First, I very happy that the

redundancy at an anchor, where the sling on one side was cut, apparently saved

lives in the "Thumb incident." But I also think they were just

lucky to have escaped with “only” severe injuries. What should they have

thought, after seeing that the hanger had already been smashed by rockfall,

knowing that they were climbing after an early-season thaw? I would argue that under

the conditions of the accident, the “expectation” of a sling getting cut by a

500 lb rock falling at least 20’, is lower than the expectation of getting

killed directly by the same rockfall.